Exploring Baffin: The Baird Expeditions

The Early Discoveries

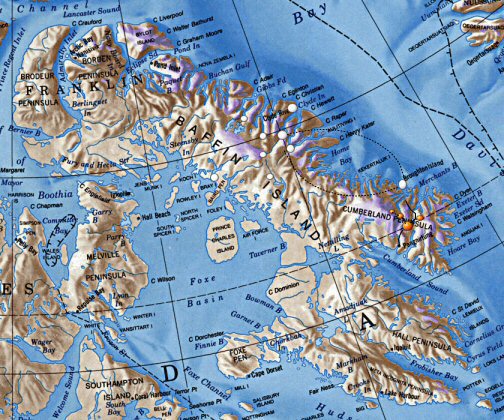

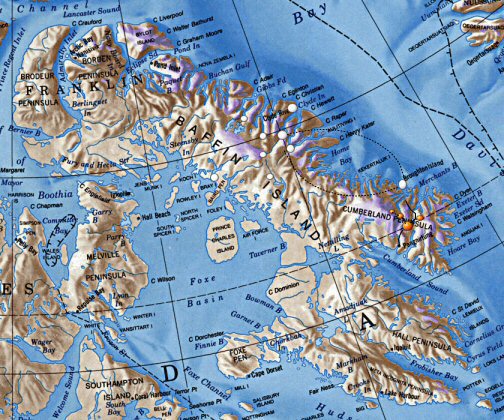

Baffin, the largest of Canadaís Arctic islands and the fifth largest island in the world, lies on the southeast corner of the Arctic Archipelago. While inhabited by the Inuit people for millennia, Baffin was first discovered by Europeans in 1576. During his search for the Northwest Passage, British explorer Martin Frobisher landed on Baffin Island near present day Iqualit. Finding iron pyrite which he mistook for gold, Frobisher undertook two more voyages to the region, with the last in 1578.

Seven years later, Frobisherís countryman John Davis charted the east coast of the island and by 1610 Henry Hudson became the first to sail through the Hudson strait on the south coast of Baffin. In 1616 William Baffin charted Frobisher Bay, ultimately lending his name to the island and discovering once and for all that the fabled Northwest Passage did not lead through Frobisher Bay.

The search for that passage continued throughout the 17th and 18th centuries as a number of explorers searched around Baffin Island for possible passages through the Arctic without success. Later surveys by the Canadian government using aircraft charted much of the interior and improved maps however by the 1950s much of the island remained sparsely populated and unstudied. The two Baird Expeditions (1950 & 1953) were an attempt by the Arctic Institute and is partners to gain a better understanding of what lay within the giant Arctic island.

The First Expedition: 1950

Pat Baird was the first director of the Arctic Institute of North America and in the early 1950s was responsible for organizing two scientific expeditions into Baffin Island. The first, in 1950, went forward with the support of the Canadian government and Air Force, the Geographical Society and a number of other private backers. It was based at Clyde on the east coast of Baffin and expanded inland to include a number of smaller research bases and observation centres.

The party was conveyed there by air, landing on the sea ice on May 19 and 20.

For 12 weeks the assembly of scientists and adventurers studied the regionís

plant life, the water, terrestrial animals and the breeding of Arctic birds.

Bairdís team consisted of glaciologists, zoologists, botanists, geologists,

Petrologists

and a host of other specialists drawn from universities

across

North American and Europe. Joining them were mountaineers from Switzerland, a

photographer from Texas and an artist from Montreal.

For transportation in the field the expedition depended almost completely on the use of the Arctic Instituteís Norseman aircraft, fitted initially with ski-wheels and later with floats. Traveling by air, the group established three main camps connected by radio transceivers. Camp A was the glaciological and meteorological station, situated on the Barnes Ice Cap 100 miles inland from the base at Clyde. Camp B was the biological headquarters, located at the head of Clyde Inlet. Camp M was the mountaineer base and was first established on Swiss Bay of Sam Ford Fiord and later moved to the head of Eglinton Fiord.

By August, longer trips were being undertaken to visit Lake Gillian and Bray Island near the west coast of the island. An important excursion to the south was also undertaken to visit Cape Searle the site of an immense colony of fulmars (a breed of Northern seabird) estimated to number between 100,000 and 500,000.

During their three months on Baffin the adventurers in the party, consisting

mostly of the Swiss mountaineers, summated 17 mountains

ranging up to nearly

6,000 feet in altitude, including the spectacular Cockscomb (5,330 feet) above

the head of Eglinton Fiord.

While climbing, they

carried out geological and glaciological studies on the surrounding the ice cap

and bedrock.

During their three months on Baffin the adventurers in the party, consisting

mostly of the Swiss mountaineers, summated 17 mountains

ranging up to nearly

6,000 feet in altitude, including the spectacular Cockscomb (5,330 feet) above

the head of Eglinton Fiord.

While climbing, they

carried out geological and glaciological studies on the surrounding the ice cap

and bedrock.

The camps were finally evacuated by the end of August. The ice-strengthened C. D. Howe picked up the party from their base at Clyde and transported them south before the onset of winter. Apart from exploring a vast swath of Canadian territory, the expedition brought back a great quantity of scientific information pertaining to nearly every aspect of the Arctic environment. The trip was such a success a second was soon being planned.

The Second Expedition: 1953

The second expedition to be organized by the Arctic Institute focused further south in the Cumberland Peninsula area and took place from May until September of 1953. The expedition was on similar lines but on a smaller scale than the previous trip.

This

region of Baffin Island had been first visited by John Davis in 1585. Yet, it

wasnít until the 1920s that Hudsonís Bay posts and RCMP stations brought traders

and explorers to the region. By the 1950s however the interior remained a blank

spot on the map and for this reason Cumberland was chosen as site for the 1953

mission.

A Norseman aircraft, flying from Churchill Manitoba, was used to establish the expedition in the field after the party and 4,000 pounds of equipment had been kindly flown to Frobisher Bay by the Canadian Air Force on May 12. The Air Force provided a great deal of assistance in moving supplies and men and also in providing the aerial reconnaissance of the area which had been conducted over the previous decade.

The main expedition camp was the Base Camp at Summit Lake in the centre of the Pangnirtung Pass at 1,300 feet. Camp A1 was established on the ice cap at 6,725 feet, and A2 at the head of Highway Glacier at 6,300 feet; the latter was later moved to A3 at 3,400 feet and subsequently all the way down the glacier to the Base Camp. The Biological Camp in Owl valley (600 feet) was established in June from a lakeside cache 1,800 feet above it, the nearest point where the aircraft could land. A mountain cache was also put down at Camp M at 4,500 feet.

Again the party was made up of a diverse selection of scientists from Canada, the United States, and Britain. The Swiss-Foundation for Alpine Research again sent a team of rugged scientist-mountaineers. Eventually claiming another eight peaks, the Swiss were a group which displayed a rare combination: a love of geophysics and a desire to scale icy and uncharted Arctic mountains.

The

mountaineers and scientists spend their four months on Baffin studying the

regionís flora and fauna, its geology and the Penny Icecap. The party traveled

largely by foot, ski, and large man-hauled sleds. Over the course of the

expedition, the scientists traveled the full length of Pangnirtung Pass, Highway

Glacier from the pass to the ice cap, and June River to Padle Fiord. An initial

dog-team trip in the Padloping area gave two McGill scientists a chance to

examine the birds and rocks of that region.

The

mountaineers and scientists spend their four months on Baffin studying the

regionís flora and fauna, its geology and the Penny Icecap. The party traveled

largely by foot, ski, and large man-hauled sleds. Over the course of the

expedition, the scientists traveled the full length of Pangnirtung Pass, Highway

Glacier from the pass to the ice cap, and June River to Padle Fiord. An initial

dog-team trip in the Padloping area gave two McGill scientists a chance to

examine the birds and rocks of that region.

The trip was considered a success and the camps were evacuated in August with the personnel sailing from Pangnirtung for Montreal aboard the C.D. Howe. That success had come at a high cost however as Ben Battle, a Geomorphologist and Senior Fellow in the McGill University-Arctic Institute Carnegie program, was accidentally drowned on July 13 near the Base Camp. Battle remains interred on the glacial ridge overlooking the finest part of the pass where he had worked.

For a more detailed account of the Baird Expeditions, please read the Arctic Institute's Field Reports:

First Expedition, Clyde Region, 1950.

Second Expedition, Cumberland Peninsula, 1953